-

Courses

Courses

Choosing a course is one of the most important decisions you'll ever make! View our courses and see what our students and lecturers have to say about the courses you are interested in at the links below.

-

University Life

University Life

Each year more than 4,000 choose University of Galway as their University of choice. Find out what life at University of Galway is all about here.

-

About University of Galway

About University of Galway

Since 1845, University of Galway has been sharing the highest quality teaching and research with Ireland and the world. Find out what makes our University so special – from our distinguished history to the latest news and campus developments.

-

Colleges & Schools

Colleges & Schools

University of Galway has earned international recognition as a research-led university with a commitment to top quality teaching across a range of key areas of expertise.

-

Research & Innovation

Research & Innovation

University of Galway’s vibrant research community take on some of the most pressing challenges of our times.

-

Business & Industry

Guiding Breakthrough Research at University of Galway

We explore and facilitate commercial opportunities for the research community at University of Galway, as well as facilitating industry partnership.

-

Alumni & Friends

Alumni & Friends

There are 128,000 University of Galway alumni worldwide. Stay connected to your alumni community! Join our social networks and update your details online.

-

Community Engagement

Community Engagement

At University of Galway, we believe that the best learning takes place when you apply what you learn in a real world context. That's why many of our courses include work placements or community projects.

An Gaodhal

Leagan Gaeilge | How to Search | Credits

An Gaodhal (1881-1898)

An Gaodhal was the first newspaper dedicated to readers of the Irish language. It was a bilingual newspaper that was published monthly in Brooklyn, New York, at the end of the nineteenth century. Michael J. Logan (1836-1899) was the founder, editor, and printer of the newspaper.

Who was Michael J. Logan?

In his own time, Michael J. Logan was recognised as a pioneer. The Irish World newspaper called him the “Father of the Irish Language Movement in America” and he was the first secretary of the Gaelic League in America.

He was born Micheál Ó Lócháin (Michael Loughan) on 29 September 1836 in Curraghaderry near Milltown in the north of County Galway. He was the son of a farmer. His parents’ names are thought to have been Patrick Loughan and Bridget Hession, daughter of James Hession of Garrymore over the county border in Mayo. James manufactured haircloth.

Michael’s brother Patrick (c.1829-1899) would later take on the farm at Curraghaderry. He married Mary Dowd (1844-1935) in 1865. The Loughan brothers of Curraghaderry had first cousins in Ballyweela, Co. Mayo, Rev. Mark Eagleton (c.1852-1908), parish priest of Corofin, Co. Galway, and Dr John Eagleton (c.1862-1888), who died young in An Cheathrú Rua when he contracted typhus in Leitir Móir.

Michael relayed that he attended school from the age of nine to eighteen years, and that his last schoolteacher, Peter Duggan, had trained at St. Patrick’s College in Maynooth. His brother John Duggan spent some years farming 125 acres in Carrownageeha, next to Curraghaderry, before he was evicted from his house. John’s son Patrick Duggan (1813-1896) attended St. Jarlath’s College before going to Maynooth. As parish priest and as bishop, he was a staunch defender of the lower classes, their land rights, and the nationalist cause.

On 29 July 1859, Michael Loughan married Mary Sharman (1839-1909), daughter of Charles Sharman and Anne Aughey in Kells, Co. Meath. They had five children: Mary Margaret, Anna, Bridget Catherine, Charles Thomas, and Edward J. The family lived in Doonane, Co. Laois, on the border of County Carlow before moving to America in 1871 where the youngest child was born in Brooklyn.

|

|---|

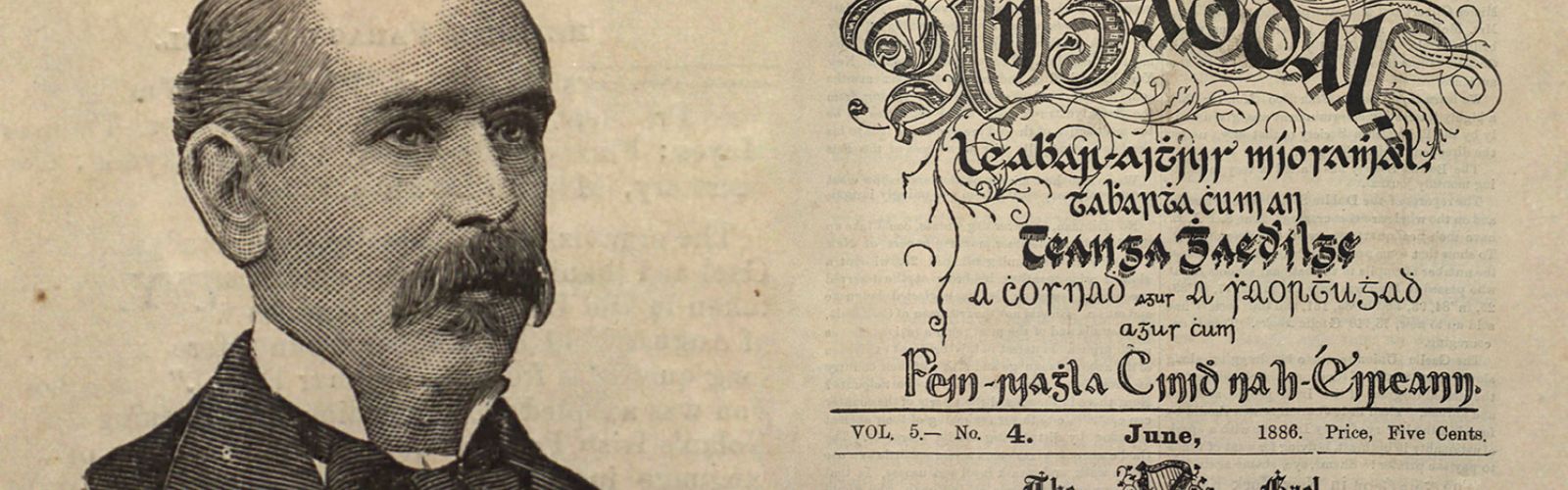

| Michael J. Logan. Image from The Gael, 18, no.1 (March 1899): 4. Catholica Collection. Digital Library@Villanova University. Falvey Library, Villanova University. |

A twist of fate and emigration

From 1853 onward, Michael Loughan spent eighteen years in the Royal Irish Constabulary as a Sub-Constable (no. 17,281) in the province of Leinster until he was dismissed from his post by the autumn of 1871. The reason cited for his dismissal — “Writing letters on the conduct of his officers” — suggests that Loughan attempted to blow the whistle on the misconduct of senior policemen and that his effort backfired on him. Whatever the reason for the report, by the end of the same year the Loughan family had emigrated to America.

Michael may have shielded his young family from the reason for leaving Ireland. Whether the family surname changed accidentally or deliberately, from ‘Loughan’ in Ireland to ‘Logan’ in America, is not known. His grandson, Rev. Joseph V. Nichols (1896-1960), parish priest in Garden City, Long Island, New York, understood from his mother Anna Logan that his grandparents had been teachers in private schools in Dublin before moving to America. However, his recollection is refuted by the evidence cited above, which could also explain the moral tone present from time to time in An Gaodhal.

Logan in America

Within a year of his moving to America, The Irish World reported that Michael J. Logan had been appointed principal of Our Lady of Victory School in Brooklyn. Logan himself stated that, upon arrival in America, he first worked as a teacher, he spent five years teaching, and he gained a teaching qualification. In census returns from 1875 onwards, however, he is described as a real estate agent. City directories from 1873 onwards concur with the evidence of census returns.

The family lived at various addresses in Brooklyn: 763 Atlantic Avenue; 814 Pacific St; and 247 Kosciusko St. Logan was a faithful Catholic and secretary of his parish temperance society. It was, however, his formidable work for the Irish language that earned him widespread respect. In 1879, the Philo-Celtic societies of Brooklyn and New York together bestowed him with a gift of an inscribed gold watch and chain as a mark of appreciation for his dedication to teaching the Irish language, work he did in a voluntary capacity. Soon after he launched An Gaodhal, in December 1881 the Brooklyn Philo-Celtic Society Orchestral Union gifted him a gold pen and inkstand, ‘in token, as set forth in the address, of his zeal in cultivating and preserving the national language and music of Ireland’ (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 30 December 1881, 4).

Michael’s daughter, Bridget C. Logan (1864-1910), later became a schoolteacher in the city. His youngest son Edward J. Logan (1873-1935) became a printer. Edward J.’s son, Edward Aloysius (1899-1958), became a compositor and his other son, Richard (1907-1980), became a policeman. Edward Aloysius married a policeman’s daughter. It might be said of Logan’s grandchildren – the teacher, the printer, the policeman, and the priest – that the apple did not fall far from the tree.

The Irish language in America in the late nineteenth century

|

|---|

|

“The Exile from Erin” by Jack B. Yeats, from the book Irishmen All by George A. Birmingham (published 1913). © Estate of Jack B. Yeats, DACS London / IVARO Dublin, 2023. |

On 24 August 1869, John O’Mahony, editor of The Irish People, which was published in New York, wrote: “Brooklyn contains as many persons who speak our vernacular Gaelic as Cork City.” From that point in time to the end of the century, the number of Irish speakers in America rose until it reached its zenith in the 1880s and 1890s. Estimates suggest that, in the 1890s, 40% of the world’s Irish speakers were living outside of Ireland. Of those, an estimated 400,000 lived in America and 70,000 of those lived in the New York area. With so many speakers converging on urban centres where they could encounter the latest technology including printing, it comes as no surprise that the world’s first newspaper dedicated to readers of Irish should emerge in Brooklyn.

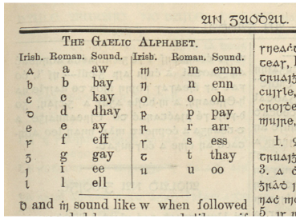

Irish-American Newspapers

Literacy levels among those who emigrated from Ireland in the nineteenth century were often limited and, among those, where native speakers of Irish were literate, it was typically only in English. Consequently, newspapers published by and for the Irish in America were, for a long time, in English, with the exception of a number of newspapers including The Irish People, The Irish American, The Monitor, The Citizen, and The American Celt, which dedicated some inches in ‘Gaelic columns’ to Irish language content. Irish-American newspapers often relied on roman type in place of Cló Gaelach type (Irish script), where a fount of such type, or a compositor able to comprehend it, was unavailable.

Michael J. Logan was the catalyst for the changes that would ensue. On 25 May 1872, having spent only a few months in America, Logan wrote to the Irish-American newspaper with the greatest circulation, The Irish World, urging the establishment of Irish language classes that would enable Irish speakers to gain literacy and learners to acquire the language. Voicing concern about bad behaviour among certain members of the Irish community in America, Logan believed the acquisition of language and literacy would inspire greater self-respect. By March 1873, he had organised Irish language classes for free in Brooklyn. He continued to offer evening classes over many years.

Philo-Celtic Societies

|

|---|

|

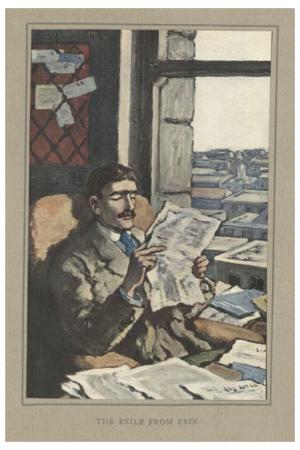

Minutes of the Philadelphia Philo-Celtic Society, Daniel J. Murphy Collection. Courtesy of University of Galway Library. |

Logan’s efforts inspired other people including P. J. O’Daly in Boston. The first Philo-Celtic Society was established there on 21 April 1873 with O’Daly serving as secretary. Logan was among those who established a branch in Brooklyn in late 1874. In 1878, another branch was formed in New York (the two cities were independent of each other until they were consolidated in 1899). With the help of these societies, Irish people on both sides of the Atlantic were inspired to sustain and nourish their language and culture. By 1876, it was believed that more than 1,000 people were attending Irish language classes all over the New York area. The strategies of the Philo-Celtic Societies provided a template for the Gaelic League later.

Establishing the newspaper An Gaodhal

An Gaodhal was established under the auspices of the Brooklyn Philo-Celtic Society and, from the beginning, Michael J. Logan was its editor. Reflecting on the first issue released in October 1881, Matthew Knight says: “It was not a fancy production, nor did it need to be; An Gaodhal represented a humble conclusion to a decade of incitement, propagation, and patriotic exertion on behalf of the Irish language in America.” By the time the fourth issue was released, however, professional printing of the newspaper was proving too costly and the entreprise risked folding for want of sufficient funds. So that the publication would persist, Logan decided to take up the task of printing the newspaper himself, alongside the task of editing it.

Early in 1882, it appears that the necessary printing equipment was installed in Logan’s office and that he instantly applied himself to the craft of printing with the help of a manual called Watson’s Amateur Printer. From then on, his days were spent with real estate, and his nights either with preparing the newspaper or teaching Irish. He continued diligently issuing the newspaper monthly, more or less, until his death. He earned no money from this work and the newspaper survived on advertising and subscriptions. In her comprehensive study of the newspaper, Mícheál Ó Lócháin agus An Gaodhal, Fionnuala Uí Fhlannagáin observes that Logan refused an offer of $5,000 to improve the newspaper: “bhí a neamhspleáchas thar a bheith tábhachtach dó” – “his independence was very important to him.”

-250x375.png) |

|---|

|

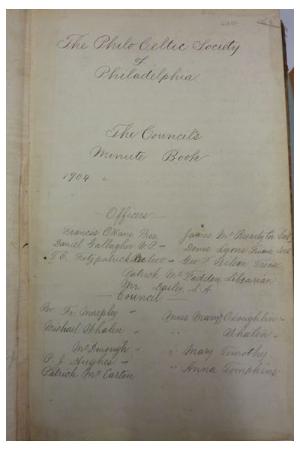

Front page of the newspaper. Courtesy of University of Galway Library. |

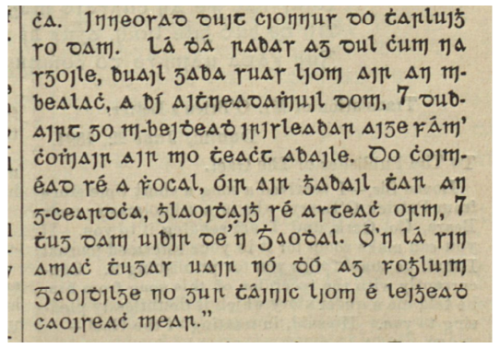

In its first year, An Gaodhal gained 1,257 subscribers all over the world including Australia, New Zealand, Alaska, France, Germany, England, Scotland, and Mexico. Other newspapers helped highlight An Gaodhal. At its peak, the newspaper had a subscription base of nearly 3,000. An Gaodhal was popular among language learners because its pages typically featured two columns each with Irish and English translations appearing side by side. Among those who attributed their ability to read Irish to An Gaodhal was the writer Pádraig Ó Laoghaire (1870-1896) from Inches in the Beara Peninsula, Co. Cork:

“Lá dhá rabhas ag dul chum na sgoile, bhuail gabha suas liom air an mbealach, a bhí aithneadamhuil dom, & dubhairt go m-beidheadh irisleabhar aige fám’ chomhair air mo theacht abhaile. Do choiméad sé a fhocal, óir air ghabhail thar an g-ceardcha, ghlaoidhaigh sé asteach orm, & thug dam uibhir de’n Ghaodhal. Ó’n lá sin amach thugas uair nó dhó ag foghluim Gaoidhilge no gur tháinic liom é leigheadh caoiseach mear.”

“One day I was going to school, I met a blacksmith who was known to me on the way and he said he would have a journal for me on my return home. He kept his word, for, as I passed the forge, he called me in, and gave me an issue of An Gaodhal. From that day on I spent an hour or two learning Irish until I was able to read it fairly quickly.”

Content of An Gaodhal

The content of An Gaodhal includes articles, letters, advertisements, lists of subscribers, folklore, poetry, and songs. According to Máirín Nic Eoin, An Gaodhal was not as handsome or substantial as other journals of the period nor was its editorial scope as broad. However, it placed a remarkable emphasis on contributions from readers, whether letters, prose, poetry, or songs. In addition, Logan promoted the preservation and discussion of literature in Irish, written and oral, old or newly-composed; and he encouraged the teaching and learning of the language and included translations to serve those goals. Consequently, as Nic Eoin observes: “the value of An Gaodhal as a historical source may lie less in its overt journalistic content and more in its function as a community directory and a non-elite forum of cultural communication” (2014). Logan adopted the moniker ‘Éire Mhór’ to identify the network of Irish speakers all over America.

|

|---|

|

Extract from An Gaodhal, 8, no. 10 (September 1891): 119. Courtesy of University of Galway Library |

Challenges and determination

|

|---|

| Courtesy of University of Galway Library. |

Given Logan worked on his own initiative, there were times when he failed to achieve the desired standard of editing. He wrote:

“The GAEL has many typographical errors for the want of sufficient time to properly scrutinize it. As has been observed in another column, our regular business occupies our time every day until five o’clock in the evening: two evenings in the week are devoted to the P. C. [Philo-Celtic] Society, and the remaining evenings to writing and translating the matter and setting up the type for these twelve pages; but we paid too much money for the getting up of the title page to let it go without paying considerable attention to it, and we assure our readers that it is, at least, as correct as the English translation. We have the same amount of knowledge of Irish that we have of English, no more nor no less. We deem this statement to be due to our readers.”

In the same period, controversy surrounded the question of typeface: was it better to print Irish in the Irish script or in roman type? Sometimes it proved challenging to source a fount of type or a compositor capable of setting Irish script. Logan wrote:

“Seeing our inability to prepare the sixteen pages of the Gael monthly owing to the difficulty of securing competent Gaelic compositors, and being overwhelmed with complaints because of its irregular appearance, we had come to the conclusion it would be more agreeable to the reader to reduce the paper in size and receive it every month regularly. But being chafed by old Gaelic friends, particularly, our esteemed Brother, F S M’Cosker, of Mobile, on the shrinkage, and lest it should be assumed as an indication of decay in the Gaelic Movement (which is quite the reverse), we have changed our mind, and henceforth the Gael will be out in its usual size, and regularly every month, if we can. Do our Gaelic friends know that the six pages of Gaelic matter usually in the Gael would cost as much for composition as twenty-four pages of English matter?”

|

|---|

|

This instructive table appeared frequently in An Gaodhal. Courtesy of University of Galway Library. |

Logan remained steadfast. Again and again, the newspaper reveals the belief that grounded his commitment: wherever a small gap needed to be filled when typesetting, he would print the slogan “Beidh an Ghaedhilge faoi mheas fós” – “Irish will be respected yet.” Speaking in 1969, Máirtín Ó Cadhain declared that Logan never received the respect due to him “considering how much An Craoibhín [Douglas Hyde], the Irish language movement, and the nationalist movement too, owed to his teachings” – “as ucht a mhéid is a bhí an Craoibhín, gluaiseacht na Gaeilge agus an ghluaiseacht náisiúnta freisin faoi chomaoin ag a chuid teagaisc.”

How An Gaodhal was received

Máirtín Ó Cadhain described the variety of Irish in An Gaodhal as ‘rustic’: “Gaeilge thíriúil a bhí sa Ghaodhal.” This linguistic style, emerging from lived experience, was likely attractive to those accustomed to hearing Irish. In any case, the number of subscribers increased to 3,000 thanks to the support of editors such as Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa who urged readers of his own newspaper, The United Irishman, to support An Gaodhal.

On 7 December 1883, the editors of the Dublin newspaper Freeman’s Journal expressed their regard for An Gaodhal: “This publication is remarkable in many ways. It gives proof of the strong spirit of nationality animating our countrymen in the U.S. and of the great regard that is gradually growing up there for the Irish language.” The content of An Gaodhal also proved compelling. In February 1884, one reader, Fr. D. B. Mulcahy in Ballintoy, Co. Antrim, wrote to Logan: “Everything in the Gael is read here as if it were a letter from a daughter in America to an anxious father in Ireland.”

Most significant of all was the impact the newspaper had on the Irish language movement more broadly. When An Gaodhal was created, it inspired a language community to write and to act, as Regina Uí Chollatáin explains: "The creation of an international authorship in nineteenth-century Irish-language journalism in turn nurtured the creation of a modern Irish literature and the extension of the use of the Irish language in national and transnational dialogues. The success of this was to be realised through the implementation of the Revival process in the twentieth century" (2020, 376). According to Máirtín Ó Cadhain, An Gaodhal published ‘the first sentence in modern Irish literature, a literature still forming itself to this very day from courage and hope’ – “an chéad abairt i litríocht nua-aimsire na Gaeilge, litríocht arb as misneach agus dóchas atá sí á hoiliúint féin go dtí an lá inniu.”

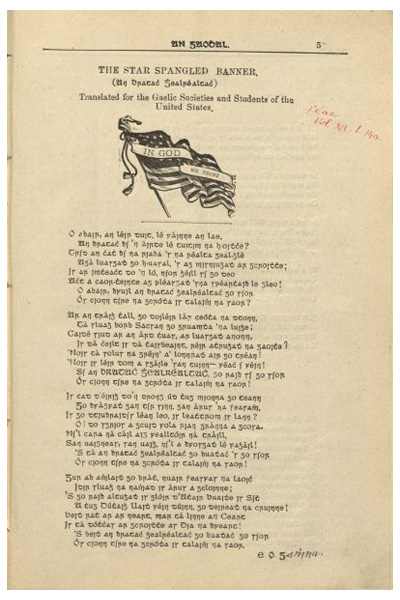

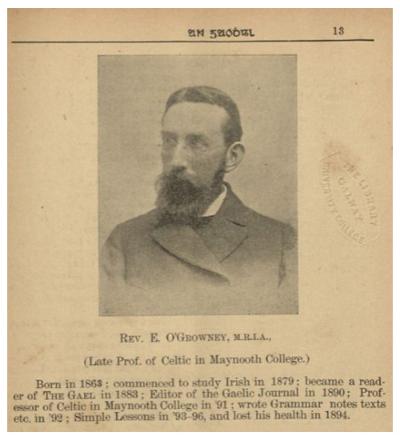

Fr. Eugene O’Growney Visit

On 16 November 1894, a special guest stayed with the Logan family at 247 Kosciusko St in Brooklyn. Fr. Eugene O’Growney (1863-1899) had arrived in New York the night before, poor health having brought the young priest from Ballyfallon, Co. Meath, to America. In the December 1894 issue of An Gaodhal, Logan described the great welcome for Fr. O’Growney at the dockside in New York:

“Father O'Growney arrived here by the Teutonic on the 15th inst. The vessel was expected on the 14th, so that the uncertainty of landing caused a great disappointment to a good many Gaels (the editor of this paper being one of them) who expected to meet him at the dock and greet him with a genuine Ceud míle fáilte. Nevertheless, he was not permitted to land alone, the ubiquitous Gael was there — Father Murphy, who came specially all the way from Springfield, Ohio, to greet him, and Martin J. Henehan, who came from Providence, R. I. on the same purpose, the Hon. Denis Burns, Captain Norris, and other New York Celts, were there to greet him. We now tell our Gaelic friends that though Fr. O'Growney bears the evidences of overwork, he appears to be in tolerably good health.”

|

|---|

|

Courtesy of University of Galway Library. |

From 1891 to 1894, Fr. O’Growney was editor of Irisleabhar na Gaedhilge (The Gaelic Journal), a bilingual Irish-English journal launched in Ireland in November 1882. In the March 1893 issue of that publication, O’Growney wrote about An Gaodhal: “Nothing shows the advance made in the study of Gaelic better than the quality of the popular Gaelic of the Gael of Brooklyn. Scores of people who now write Irish well and speak it too, have the little Gael to thank for much of their success.” Indeed, Logan believed An Gaodhal had prompted the establishment of Irisleabhar na Gaedhilge.

That November night in Brooklyn, O’Growney and Logan, the two editors of the Irish language periodicals of their day, had a long discussion about the Irish language movement on both sides of the Atlantic.

“From our talk with Father O'Growney on the subject, we are satisfied that the Gaelic movement in Ireland is in a tolerably good condition. — The Language is becoming fashionable there, the gentry are learning it; it is expected that, in the near future a Keltic Chair will be established (it is now in a large number of them) in all the rural Catholic colleges, and that the Irish language will be taught in all the National schools in the Irish-speaking districts. These are the leading points, or a synopsis, of Father O'Growney's report of the condition there. [...] Father O'Growney candidly acknowledges that their success in Ireland is largely, perhaps wholly, due to our exertions here in America.”

Unfortunately, neither of these great workers for the Irish language would live to old age. They died the same year, 1899, Logan in Brooklyn and O’Growney in California. The memory of O’Growney endured, in particular because of his famous series of books, Simple Lessons in Irish, extracts of which appeared as language instruction material in An Gaodhal.

An Gaodhal changing — The Gael (1899-1904)

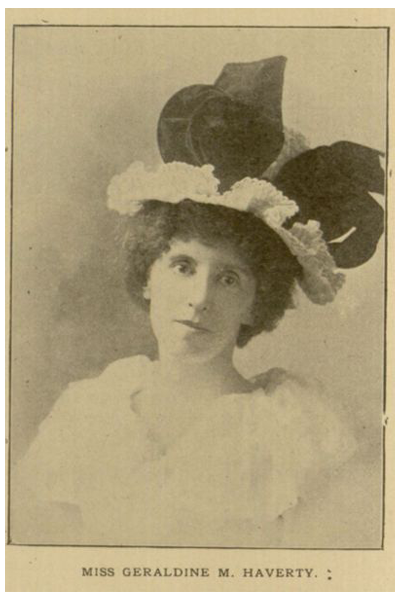

When Michael J. Logan died suddenly on 10 January 1899, his supporters determined that the newspaper and its considerable subscription base would not be abandoned. By March 1899, a new editor was appointed. Born in New Jersey, Geraldine M. Haverty (1866-1939) was a schoolteacher who spent most of her life in New York. Her father, Major Patrick M. Haverty (1827-1901) from Dublin, was a former soldier turned bookseller and publisher whose shop at 14 Barclay St, New York, was a literary centre in the city.

|

|---|

|

Geraldine M. Haverty, image from The Gael, 18, no.8 (November 1899): 228. Catholica Collection. Digital Library@Villanova University. Falvey Library, Villanova University. |

A professional publisher, Stephen J. Richardson (1851-1922) from Kinnegad, Co. Westmeath, printed the new series of the newspaper under the title The Gael. As Geraldine M. Haverty was not fluent in Irish, the newspaper was mostly in English and the amount of Irish language content declined. Language instruction for learners and letters to the editor no longer featured. The newspaper was expanded, illustrations and photographs were added, and it was regularly adorned with a colourful cover. The additional costs associated with this approach proved too great, however, and the final issue of The Gael was published in December 1904. The Gael is available online via the Falvey Library at Villanova University.

An Irish language newspaper in New York in the twentieth century

Though An Gaodhal / The Gael ceased, the story of Irish language newspapers in New York continued. In 1928, another newspaper appeared there. Guth na Gaedhilge (The Voice of the Irish Language) was a monthly bilingual Irish-English newspaper created by Patrick F. Meagher (1871-1967) from Fethard, Co. Tipperary. Meagher was a professional printer who spent many years working at the New York Times. He embarked on producing the new publication as a solo venture, taking upon himself all the necessary tasks including editing, printing, and distribution. He purchased equipment and operated from the rear of his house, 4402 Park Ave in The Bronx. However, without a sufficient number of subscriptions, the newspaper survived for just six months. By that time, the number of Irish speakers in America had fallen considerably from the high-point of of 400,000 seen at the end of the nineteenth century.

While Guth na Gaedhilge did not last as long as An Gaodhal, each of these newspapers reminds us of the power and position of media in society as well as the value of the Irish language among Irish people near and far.

How An Gaodhal survived

From 1884 onward, Rev. Daniel J. Murphy (1858-1935), who was born in Sligo and lived in Philadelphia, was reading An Gaodhal. The young priest’s first contribution to the newspaper, a short prayer, was published by Logan in 1886. Their correspondence continued for many years. Rev. Murphy moved to collect every issue of the newspaper. When he succeeded in achieving this challenging task, he collated them and bound them in hardback volumes and, in 1924, shipped them to Galway to the Professor of Irish there, Tomás Ó Máille (1880-1938). The margins of these volumes are filled with Rev. Murphy’s notes, which relate to his manuscripts, papers that followed An Gaodhal to Galway in 1936. In the National Library of Ireland, additional volumes of An Gaodhal bearing Rev. Murphy’s marginalia survive. In those volumes, the notes are exactly the same, a duplication that demonstrates the precision the learned priest accorded his work.

Resources

- Biography of Michael J. Logan in Irish

- Biography of Michael J. Logan in English

- An Gaodhal in the University of Galway Library Digital Collections

- Project blog #AnGaodhal, New York University

- Methodology blog #AnGaodhal, University of Galway

- Transkribus blog about the #AnGaodhal project

- Transkribus monolingual OCR model “An Gaodhal Gaeilge / Irish Monolingual Model”

- Transkribus bilingual OCR model “An Gaodhal Irish / English Bilingual Model”

- An Gaodhal Newspaper (1881-1898) Full-Text OCR Output Files, New York University

Further Reading

- Bailey, Peter ed. Long Island: A History of Two Great Counties Nassau and Suffolk Vol. III Personal and Family History. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., Inc., 1949, https://archive.org/details/longislandhistor03bail/page/162/mode/2up.

- Dereza, Oksana, Ní Chonghaile, Deirdre and Wolf, Nicholas, “To Have the ‘Million’ Readers Yet”: Building a Digitally Enhanced Edition of the Bilingual Irish-English Newspaper An Gaodhal (1881-1898). In: Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Language Technologies for Historical and Ancient Languages (LT4HALA) @ LREC-COLING 2024, eds. Rachele Sprugnoli and Marco Passarotti, 65-78. ELRA and ICCL.

- Farrell, Gerard. Irish, Gaelic and Roman type (Seanchló agus Cló Rómhánach) v.3. Transkribus, 2023 (accessed 1 July 2024).

- Knight, Matthew. “Gaels on the Pacific: the Irish language department in the San Francisco Monitor,1888–91.” Éire - Ireland 54, no. 3-4 (Fall/Winter 2019): 172–199.

- Knight, Matthew. “Forming and Training an Army of Vindication: The Irish Echo, 1886-1894.” In North American Gaels: Speech, Story, and Song in the Diaspora, edited by Natasha Sumner and Aidan Doyle, 163-200. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020.

- Knight, Matthew. "Our Gaelic Department": The Irish-Language Column in the New York Irish-American, 1857-1896. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2021 (accessed 12 March 2024).

- Knight, Matthew. “Champions of the Irish language in America: Daniel Magner, Thomas D. Norris, and their contributions to “our Gaelic department” in the Irish-American, 1878–1900.” Proceedings of the Harvard Colloquium Conference 40 (2023): 236–265.

- Lyons, Fiona. “Chaos or Comrades? Transatlantic Political and cultural Aspirations for Ireland in Nineteenth-century Irish American Print Media.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 39 (2019): 1919-212. Cambridge: Department of Celtic Languages & Literatures, Harvard University.

- Lyons, Fiona. Thall is abhus: Irish language revival, media and the transatlantic influence 1857-1897. Doctoral dissertation, University College Dublin, 2021.

- McGuinne, Dermot. Irish Type Design: A History of Printing Types in the Irish Character. Irish Academic Press, 1992.

- Moloney, Patricia. “Cataloguing older Irish language material: some brief notes on the Cló Gaelach.” LibFocus blagphosta, 2 April 2020 (accessed 18 February 2024).

- Ní Bhroiméil, Úna. Building Irish Identity in America, 1870-1915. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2003.

- Nic Eoin, Máirín. “Journalism or Mobilisation of Identity? Re-assessing An Gaodhal (1881-1898) as a source for the history of the Irish language in America.” Unpublished conference paper comhdhála, American Conference for Irish Studies & Canadian Association for Irish Studies, joint annual conference, University College Dublin, 11 June 2014.

- Ní Chonghaile, Deirdre, Dereza, Oksana, and Wolf, Nicholas. An Gaodhal Newspaper (1881-1898) Full-Text OCR Output Files (Version 1) [Data set]. New York University, 2023.

- Nilsen, Kenneth E. “The Irish Language in New York, 1850-1900.” In: The New York Irish, eds. Ronald H. Bayor and Timothy Meagher, 252-274. Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- Nilsen, Kenneth E. “The Irish Language in nineteenth century New York city.” In: The Multilingual Apple: Languages in New York City, eds. Ofelia Carcía and Joshua A. Fishman, 53-71. New York & Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1997.

- Nilsen, Kenneth E. “Irish Gaelic Literature in the United States.” In: American Babel: Literatures of the United States from Abnaki to Zuni, ed. Marc Shell, 177-218. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Ní Uigín, Dorothy. “An Iriseoireacht Ghaeilge i Meiriceá agus in Éirinn ag tús na hAthbheochana: An Cúlra Meiriceánach.” In: Léachtaí Cholm Cille XXVIII, ed. Ruairí Ó hUiginn, 25-47. Maigh Nuad: An Sagart, 1998.

- Ní Úrdail, Meidhbhín. Pádraig Ó Laoghaire (1870-1896): an Irish scholar from the Béarra Peninsula. Béarra: Cumann Staire Bhéarra, 2021.

- Ó Buachalla, Breandán. “An Gaodhal i Meiriceá.” In: Go Meiriceá Siar, ed. Stiofán Ó hAnnracháin, 38-56. Baile Átha Cliath: An Clóchomhar Tta. published for Cumann Merriman, 1979.

- Ó Cadhain, Máirtín. “Conradh na Gaeilge agus an Litríocht.” In: The Gaelic League Idea, ed. Seán Ó Tuama, 52-62. Cork: Mercier Press, 1972.

- Ó Ciosáin, Niall. “Print and Irish, 1570-1900: An Exception among the Celtic Languages?” Radharc 5/7 (2004-2006): 73-106.

- Ó Conchubhair, Brian. “The Gaelic Front Controversy: The Gaelic League’s (Post-Colonial) Crux.” Irish University Review 33, no. 1 (Spring-Summer 2003): 46-63.

- Ó Dochartaigh, Liam. “Nótaí ar Ghluaiseacht na Gaeilge i Meiriceá, 1872-1891. In: Go Meiriceá Siar, ed. Stiofán Ó hAnnracháin, 65-90. Baile Átha Cliath: An Clóchomhar Tta. published for Cumann Merriman, 1979.

- O’Leary, Philip. The Prose Literature of the Gaelic Revival, 1881-1921: Ideology and Innovation. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994.

- O'Neill, Timothy. The Irish hand: scribes and their manuscripts from the earliest times. Corcaigh: Cork University Press, 1984 (2014).

- Scannell, Kevin, Regan, Jim and Damazyn, Kevin. Tesseract Uncial Training Data, Github, 2020.

- Sharpe, Richard, and Hoyne, Micheál. Clóliosta: Printing in the Irish Language, 1571-1871. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2020.

- Sumner, Natasha, and Doyle, Aidan. “North American Gaels.” In North American Gaels: Speech, Story, and Song in the Diaspora, eds. Natasha Sumner and Aidan Doyle, 3-36. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020.

- Uí Chollatáin, Regina. “Irish Language Revival and ‘Cultural Chaos’: Sources and Scholars in Irish Language Journalism.” In: Proceedings of the Celtic Colloquium, 30 (2010): 273-292. Cambridge: Department of Celtic Languages & Literature, Harvard University.

- Uí Chollatáin, Regina. “The Irish-Language Press: ‘A tender plant at the best of times’? In: The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, Volume 2, ed. Walter Scott, 357-376. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

- Uí Fhlannagáin, Fionnuala. Mícheál Ó Lócháin agus An Gaodhal. Baile Átha Cliath: An Clóchomhar Tta., 1990.

- Uí Fhlannagáin, Fionnuala. Fíníní Mheiriceá agus an Ghaeilge. Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim, 2008.

- Uí Fhlannagáin, Fionnuala. Nár Fhág Ariamh mo Chuimhne: Seisear Caomhnóirí Gaeilge as Maigh Eo. Baile Átha Cliath: LeabhairCOMHAR, 2020.