History of the School of Education

"THE BEGINNINGS"

Note: The following article was written, shortly before his death in 2001, by an tAthair Eustás Ó Héideáin O.P., Professor of Education at NUI, Galway from 1968 - 1988

Note: The following article was written, shortly before his death in 2001, by an tAthair Eustás Ó Héideáin O.P., Professor of Education at NUI, Galway from 1968 - 1988

The first Professor of Education, Tomás Ó Ceallaigh, was appointed in 1914, soon after similar appointments had been made by the National University in Dublin and Cork.

Ó Ceallaigh held the Chair for only ten years. He became very ill in 1923 and his doctor advised him to go to France. He left Galway on February 4th 1924 and we are told that on his way through Dublin he met an old friend, Fr Pádraig de Brún, later to become President of UCG. Within three weeks, on 24 February, Ó Ceallaigh died in France, in San Roche Hospital, Nice and he was buried in Nice Cemetery where a Celtic cross, with a simple inscription in both Irish and English, was erected to mark his grave.

Ó Ceallaigh came to Galway with the reputation of a scholar, an outstanding, experienced teacher, and a writer, especially in Irish. An obituary in the Galway Tribune(17 May 1924) recorded another activity for which he was noted:

'When the National Loan was established some years ago Father O'Kelly's energetic work in Galway resulted in a very considerable collection which was acknowledged by the late General Michael Collins -God rest both their souls. This written acknowledgment has survived many a raid and search by the "Tans" and other enemies. Fr Tom was chosen in that time of danger for this work because he was always a man who could do what he had to do efficiently and quietly without noise or boast. A man devoid of all pretence, Fr O'Kelly preferred doing work to talking about it'.

The details of his earlier life can be summarised simply. He was born in Gurteen, Sligo, on December 15th 1879. At the age of four he went to live with his grandmother who had a considerable influence on him, passing on to him her interest and skills in Irish music, folklore and language.

At the age of thirteen he won first place in a scholarship examination to Summerhill College, Sligo. Later, in 1897, he went as a clerical student to Maynooth College, was ordained priest in 1903, and after the award of the Licentiate in Theology degree returned to Summerhill College where he taught until 1912.

In 1908, the year of the establishment of the National University of Ireland, he qualified as a Bachelor of Arts, and from 1913 to 1914 studied in University College Dublin where he was awarded the Higher Diploma in Education. In Dublin also he was Ard Ollamh in Coláiste Laighean, the Leinster College of Irish. Later (1922) he was awarded the M.A. Degree in University College Dublin.

Ó Ceallaigh's short professional life was spent in teaching, first in Summerhill College Sligo, then in Coláiste Laighean, finally in University College Galway, and those in contact with him said he was an exceptionally good teacher. His second love was Irish language, music and song. The interest given him by his grandmother ripened considerably in Maynooth under the influence of Fr Eoghan Ó Gramhnaigh who had been appointed Professor of Irish in 1891.

In Maynooth, Ó Ceallaigh taught Irish to other students, he was one of the founders of Cuallacht Chuilm Cille and Irishleabhar Mhuighe Nuadhad, and he edited Irisleabhar na Cuallachta. That was only the beginning of his literary work in Irish. His biography, An tAthair Tomás Ó Ceallaigh agus a Shaothar, by An tAthair Tomás S. Ó Laimhin (Gaillimh 1943), gives the text of twenty two poems composed by Ó Ceallaigh, two translations, and nine poems which he collected from various sources. The biography also includes six plays and five ceol-dramaí.

Here our particular interest is the period 1914-1924 during which Ó Ceal1aigh was Professor of Education in UCG. When he applied for appointment one of his referees was Dr Douglas Hyde, who wrote of him:

'Tá aithne ag gach uile Ghael a bhfuil suim aige i litríocht agus i n-oideachas na hÉireann ar an Athair Tomás Ó Ceallaigh. Agus tá meas an domhain Ghaelaigh ar a chuid filíochta agus a chuid dramaíochta gan trácht ar a léinn i gcursaí na Gaeilge' ( Applications and Testimonials for Chair of Education, 1914. Quoted, Ó Láimhin, op cit, p 5).

Another referee, Seoirse Ó Muanáin, B.L., Secretary of Coláiste Laighean, the Leinster College of Irish, wrote:

'The Rev. Thomas O'Kelly, B.A., B.D., has acted as Principal of the Leinster College of Irish for the session 1913-1914. In that capacity he has been solely responsible for the academic organisation of the classes at Dublin, Milltown and Mullingar. He has, further, been in personal charge of classes in Dublin and Milltown in Irish Literature, Advanced Phonetics and Metrics, Teaching of Texts, and Methods of Teaching. His lectures have been systematic, precise and apt. They have attracted the close attention of students who have expressed the highest appreciation of them. In a quiet manner he has preserved a high standard of order in all the arrangements. This has been greatly helped by his gentle, tactful and persuasive personal manner (Applications and Testimonials for Chair of Education,-1914. Quoted Ó Láimhin, op cit, p 20).

A third referee was Professor Timothy Corcoran, Professor of Education in University College Dublin. In the academic year 1913/14 Ó Ceallaigh studied under him for the Higher Diploma in Education, and secured first place in the examinations. Corcoran wrote:

'During the academic session 1913-'14 the Rev. Thomas O'Kelly has been constantly in attendance at my lectures at the Course prescribed in this College for the Higher Diploma in Education, established by the National University. He has also, to my knowledge, been engaged in work on our programme for the degree of M.A. in Educational Science, though unable, owing to other educational duties, to attend the special course leading to that degree. I have very great pleasure in recording, even before the end of the Academic Year, the high opinion I have formed of Father O'Kelly's knowledge and ability. His written work, submitted to me in the form of terminal essays, shows him to be able to unite in a marked degree the Theory of Education and that practical skill and judgement which come from prolonged experience in classwork' (Applications and Testimonials for Chair of Education, 1914. Quoted Ó Láimhin, op cit,p 21).

Before the appointment of Ó Ceallaigh in Galway, the National University had already filled two Chairs of Education, a Professorship of the Theory and Practice of Education in Dublin, and a Professorship of Methods of Education in Cork. The University Calendar for 1914 gives details of the Higher Diploma in Education courses approved for Dublin and Cork, and adds: 'The above conditions to apply in every respect to University College Galway, should an Education Department be formed there' (NUl Calendar 1914, p 116).

The UCG Calendar for 1915/16 (pp 87-93) gives an outline of the first UCG programme in Education.

Courses were approved for two Diplomas (the 'Higher Diploma' and the 'Diploma'), together with Education as a subject for the B.A. Degree, and the M.A. Degree programme in Educational Science.

The current, re-titled, programme of Postgraduate Diploma in Education is summarised in the Departmental 'Handbook' and here on this web site. They reflect a considerable development in the professional training of teachers, and changing needs in Irish education, since the appointment of the first Professor in 1914.

Details of the first programme (1915 - 1916) were simpler. There were five divisions:

- Philosophy in its relations to Education;

- History of Education and works of Educational writers;

- Principles of school management, organization and hygiene;

- General and special teaching methods;

- 'Other exercises'.

The material studied in the first two divisions -Philosophy and History of Education -was substantial, and typical of what would be covered in good university courses.

The last two divisions -'general and special teaching methods' and 'other exercises' -reflect an emphasis from the beginning on the practical, professional nature of the Higher Diploma programme. The 'other exercises' are listed in some detail: the preparation under direction of at least two papers during each term on educational questions; the preparation under direction of plans of work and of notes of lessons; participation in criticism lessons and in model lessons; and teaching under supervision and direction. Candidates for the Higher Diploma were to teach for at least one hundred hours during the year preceding the completion of the course and they were 'strongly advised to make arrangements for undertaking regular work as teachers, extending over the whole school year preceding the completion of the course, and amounting to about two hundred hours in all'.

When Tomás Ó Ceallaigh was appointed Professor of Education, the minimum number of teaching hours was one hundred, as in Dublin and Cork, and a period of about two hundred hours was 'strongly advised.

It is interesting that the University (NUI Calendar, 1914, p 116) accepted teaching practice in 'the Senior Division of an Elementary School having at least 20 pupils in the Senior Division, for a period of at least half a year, during which not less than one hundred lessons have been taught by each candidate'

Although it has developed considerably, the Higher Diploma programme today includes the basics of the first programme of 1915.

Teaching practice under supervision and direction is naturally included in both programmes. Also common, to quote the UCG 1916/7 Calendar (p 89), is 'the preparation, under direction, of plans of work and of notes of lessons; participation in criticism lessons and in discussions in model lessons; teaching, under supervision and direction, for at least one hundred hours, during the year preceding the completion of the course'.

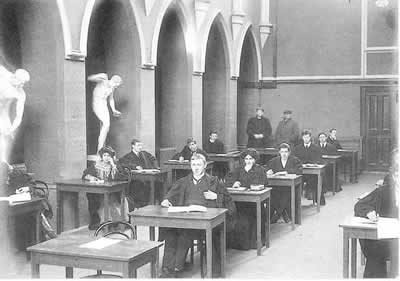

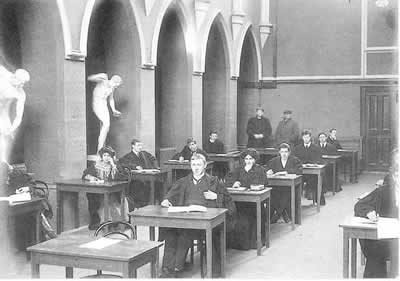

Examination candidates, Aula Maxima 1909

A footnote in the 1916/7 Calendar reflects a debt to local schools extending over eighty years: 'Facilities for class-room practice are provided in Galway by arrangements with the Heads of the various Educational Establishments.

Today however there is a provision for practice teaching not in one but in two ways: 'sequential', teaching throughout the year; and 'block release', teaching during a block' of weeks in each of the two semesters. The 'block release' programme is a UCG innovation in the professional training of secondary teachers in Ireland.

The course content of the Postgraduate Diploma in Education programme today is significantly more substantial than it was under the first Professor of Education.

Eight foundation courses are followed by all students regardless of their specialised teaching subjects: General Skills of Teaching; Curriculum and Assessment; Education Technology; Educational Psychology; Philosophy of Education; History of Education; Education and Society; Equity in Education, issues and strategies. The specific skills of teaching individual school subjects to pupils in each age group, and at varying levels of learning ability, are covered in separate tutorials on 'Special Teaching Methods'. Provision is made also for supplementary studies in science and modern languages and for elective courses in areas complementary to a teacher's responsibility in school.

On the foundation laid by the University's first Professor of Education in 1914, impressive structures have now been built for the professional education and training of teachers.

^ Hide answer

Of particular interest in the early development of the School of Education and the University was the offer of Education as a subject, not only at Diploma and postgraduate levels, but as one of the subjects for the B.A. (Ordinary) Degree. The provision is noted in the 1915/16 Calendar of the College:

'The course in Education for the Ordinary Degree of B.A. extends over two years. Three lectures on the course are given each week. The subject-matter of the course is the same as that prescribed for the Diploma in Education. At the degree examination the whole of the special subjects and special branches of method, as lectured on during the two preceding years, must be presented by each candidate'.

The mid-twenties were an anxious period for UCG. It was the smallest university college in the new State, and there was a suggestion that it might be closed. Two developments are said to have helped it to survive:

a commitment to the Irish language, the teaching of Irish and teaching through Irish;

and the decision of the College to provide an evening/weekend degree course for National Teachers.

The commitment to the Irish language, later enshrined in the University College Galway Act, 1929, was a strong cultural and political reason for supporting the College. The new degree programme for National Teachers helped to provide the increase in student numbers the College needed.

Only 246 students were enrolled in the College during the session 1926/7 (UCG Calendar 1927/8, pp 305 ff). Numbers were low enough for each student to be individually named in less than three pages of the Calendar.

The Course for National Teachers, however, opened in the session 1927/8. The increase of student numbers that year was 23.2 % , compared with the previous session. The annual increase in 1928/9 and 1929/30 was 24.% and 21 % respectively. Compared with 1926/7, the increase of student numbers in 1929/30 was 85.4 %, a significant development for a small college.

One of the students enrolled in 1926/7 on the first year of the course for National Teachers was the late Bro Leonard McCabe, N.T., B.A., H.Dip. Ed., later awarded an honorary M.Ed. Degree by the University. The grounds for the award were a long productive period as a teacher and Principal in the local Patrician Brothers school and the significant contribution he had made as Tutor and Supervisor of teaching practice in the UCG Education Department. Later under Professor Patrick Larkin who succeeded Professor Tomas Ó Ceallaigh, Bro Leonard directed teaching 'demonstration' classes in his school, locally known as 'The Bish', for Higher Diploma students.

For many years three subjects only, Irish, Celtic Archaeology and Education, were offered on the evening/weekend Degree courses, and lectures were accepted by these Departments as a normal part of their teaching commitments. Decades later, with this as a foundation, a much wider, more extensive programme of evening courses was introduced by the College.

^ Hide answer

Almost seventy years ago the University College Galway Act 1929 noted that the College 'has lately made provision by statute for securing that certain of the professors and lecturers of the said College shall deliver their lectures in the Irish language and proposes to take such further steps as circumstances may permit to secure that an increasing proportion of the academic and administrative functions of the said College shall be performed through the medium of the Irish language'.

Almost seventy years ago the University College Galway Act 1929 noted that the College 'has lately made provision by statute for securing that certain of the professors and lecturers of the said College shall deliver their lectures in the Irish language and proposes to take such further steps as circumstances may permit to secure that an increasing proportion of the academic and administrative functions of the said College shall be performed through the medium of the Irish language'.

Two years later, Autumn 1931, the College appointed An tAthair Padraig E. Mac Fhinn, D.D., M.A., A.T.O., as 'Lecturer in Education (through Irish)'. He held this appointment until he retired in 1965. He died in 1987.

An tAthair Eric, as he was affectionately known both inside and outside the College, was born in Cluain Tuaiscirt, Ballinasloe, in 1895. In many ways he resembled Tomás Ó Ceallaigh, especially in his lifelong interest in Irish language and his many publications in Irish. The centenary issue of Gearrbhaile, published in 1992, contains a short biography of An tAthair Eric, by Mairtin 0 Flaitheartaigh, and a list of over fifty publications in Irish, mainly articles, in Irish, beginning with a contribution to An Claidheamh Soluis in August 1910 and dating up through the seventies..

Apart from his provision of H.Dip.Ed. courses through Irish, and his personal supervision of students on teaching practice over a wide area "An tAthair Eric made an extraordinary contribution to the monthly journal Ar Aghaidh, founded by his friend An tOllamh Liam Ó Buachalla in March 1931. In the beginning he was an occasional contributor, but later he became editor (although he preferred the title "runaidhe Ar Aghaidh' ), business manager and distributor. Riding his bicycle, with a bundle of journals on the carrier, he personally delivered them to homes in Connemara.

The full story of Ar Aghaidh has yet to be written. It is said to have encouraged and inspired many young writers, including Sean Ó Riordain, Mairtin 0 Direain, Muiris

Suilleabhain, Eoghan 0 Tuairisc, Donal Mac Amhlaigh, and Risteard 0 Glaisne.

As for the general contents and influence of the journal, Nan Bean Ui Fhatharta, a long time friend of An tAthair Eric has written:

'Readers were educated through articles on many different subjects: books, economics, agriculture, nature, environment, history, archaeology, geography, home economics, writing, medical matters, Celtic languages and D.I.Y, when there weren't the same educational opportunities in the country as there are at present. The paper provided pleasant practical reading material for young and old alike in the Gaeltacht, in the form of poetry, folklore stories, articles about foreign countries, languages...' (Nan Ui Fhathartaigh, from typescript copy of a lecture).

An tAthair Eric is still well remembered by senior staff in the College. When he retired in 1965, there was wide support on campus for his appointment as Associate Professor of Education, a tribute to his long service in the University. But a legal difficulty emerged: a retired member of staff could not be appointed Associate Professor. When he heard about the move to honour him in this way, his comment was typical, something like this: "Seafoid! Ce uaidh a theastodh Ollunacht"

^ Hide answer

Students enrolling on the Higher Diploma in Education had sometimes wondered why it is called the 'higher' diploma when no other or 'lower' diploma was mentioned in the College Calendar. The explanation was simple. Originally, and for many decades, two diplomas were on offer side by side, a 'higher' and what one might call a 'lower' diploma.

The simple Diploma in Education again reflected the interest of the College, and of the University, in National (Primary) Teachers. The UCG Calendar, 1915/16 (p 89) said the first condition for enrolment on the course was that students 'shall have completed satisfactorily a two year course of training in a Training College recognised by the Board of National Education, or such other training Course as the University may accept as equivalent thereto'.

The programme extended over three terms, and covered both general and professional subjects. The general subjects included any three of the following first year courses: modern Irish, English, French, Latin, Mathematics, Logic, Modern History, Experimental Physics, Chemistry, Botany, and Zoology.

The broad outlines of the professional subjects (details were given in the UCG 1915/16 Calendar) were 'philosophy applied to education', 'history of education since the close of the middle ages', and 'general education method and organisation, with their special application to important branches of the school curriculum'.

Because it no longer met any real need the Diploma was withdrawn in the College some years ago. But the title 'Higher' Diploma in Education remained.

^ Hide answer

Also available from the beginning was a programme leading to the award of the M.A. Degree in Educational Science. Some details are given in the UCG Calendar, 1915/6 (pp 91-93).

The Degree course was divided into two 'classes', one extending over three terms, the other over 'at least six terms' after the B.A. Degree. Both involved further study in Psychology, Educational Theory, History of Education, and Educational Practice, and both prescribed the preparation of a dissertation. The guide lines for Class 1 Degree require that the dissertation should lie within the departments of study specified for the Degree or in cognate studies; and it should be 'of such scope as to afford adequate opportunity for the treatments of philosophical principles and methods, of historical development, and of contemporary practice related to the topics selected'.

In the case of the two-year course, 'the subject matter of the dissertation to be presented should lie within the departments of study specified for the Examination or in cognate studies'.

Only the two-year programme includes a 'study of 'the subject- matter of the course prescribed for the Higher Diploma in Education in respect of the academic year next preceding the Examination for the M.A. Degree'. Candidates who had already been awarded the Higher Diploma were exempt from examination in this area.

Again, there has been considerable development in postgraduate programmes in Education. The original M.A. Degree programme in Educational Science has been replaced by a diversity of programmes leading to the Degree Master of Education. They are cyclical, part-time degree programmes comprising course work and research dissertation. According to the official guidelines issued by the College Education Department, the Degree is intended as 'as advanced in-career, professional degree which builds upon a candidate's practical experience in education. It is designed for teachers, administrators and other educationalists interested in pursuing careers of leadership within schools, administrative, managerial or curricular bodies and also in community education programmes...The programme is modular and comprises eight obligatory core modules and six elective modules plus a research dissertation'

Facilities have also been available for research leading to the Ph D Degree.

^ Hide answer

Had Tomás Ó Ceallaigh, the first Professor of Education, and his immediate successor Professor Patrick Larkin, been able to foresee the present day from the early twenties, they would have been happy with what has been built on the foundations they laid. The Department of Education (now School of Education) has been a leader in several third level innovations in Education.

|

Prof. Pat Larkin

|

The Department has pioneered for example, an M Ed Degree programme, in co-operation with other College Departments, offering graduate teachers an opportunity to do significant supplementary study in their teaching subject together with studies in Education.

At Higher Diploma in Education level, two centres which were established in the Department were Irish leaders in their respective areas of specialisation.

In recognition of the growing importance of science in the post-Sputnik era of the late 1960s the Department appointed Mr Jim Christian to develop the teaching of science at second level by providing a centre where practical lessons in the teaching of Biology, Physics and Chemistry could be demonstrated in a dedicated location. Later, when Mr Jim Christian became Director of Thomond College, this work was continued by Dr Oliver Ryan.

Following a visit to the USA in the early 1970s, Dr Kieran Woodman established a comprehensive and practical hands-on course in Audio Visual Aids for the then Higher Diploma in Education students, the first such formal course in Ireland at that time. Later this course was to provide the impetus for the establishment, under the direction of Mr Victor Davis, of the Educational Technology Centre, with its Tutorial rooms, Graphics Room and Resource Library. Computers were later to play a major role in this area. This has since been developed further by Dr Tony Hall and his team which now incorporates the Apple iPedagogy Learning Environment, providing a creative environment for student teachers to develop new ways to engage pupils with the curriculum.

Micro-teaching, pioneered at Stanford University in the USA and known as the 'Stanford Model' offered an effective method of learning the skills of teaching. It was introduced into the Department in 1974, together with 'Block Release' teaching practice which was already in use in Ireland for National teachers in training, but was now used for colleagues in second level schools.

The sole Higher Diploma in Education was then joined by other Diploma and Certificate courses. A Certificate programme in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) was pioneered here by Dr Oliver Ryan and provided specialised knowledge and skills, particularly for Irish teachers working abroad. It could be taken as a part-time course during the academic year, or as an intensive summer course in July. An advanced Higher Diploma TEFL course was also offered. This course was organised and run by the Department of Education in conjunction with the then Adult and Continuing Education office.

A second Higher Diploma - in Remedial Education - was introduced as an in-service course for teachers, giving them the specialised knowledge and skills needed for an effective approach to remedial education. This Higher Diploma was officially recognised by the State Department of Education as a qualification for remedial and resource teaching posts in first and second level schools. It has since been expanded and re-named as the Postgraduate Diploma (Special Education Needs).

The Education Department, as it used to be known, was also closely involved in the design, development and coordination of the TEMPUS programme which has focused on East European countries, especially Poland and Russia. Developed, organised and led by Dr Oliver Ryan, four main areas were identified: training of student teachers, in-service courses for teaching staff, curriculum development, and the technology of education. Some ten groups of Polish and Russian teachers and lecturers were welcomed to the University, from periods from one to three months. The School of Education has also shared in College-wide ERASMUS programmes.

On a national level, the successful Educational Studies Association of Ireland had its origin in Galway in 1977, when two young UCG postgraduates in Education, John Marshall in Galway and Jim McKiernan at Queen's University, Belfast, organised the first conference on campus. This proved the need for such an association in Ireland, and led to its formal constitution the following year.

The then Department co-operated closely in the process that led to the acceptance (1977) of St Angela's College of Home Economics, Sligo, as a Recognised College of the National University. Third year students of the College spent a period of time on the Galway Campus, for supplementary studies in Education, Educational Technology and Science.

The above is only a summary of the beginnings of the UCG/NUI, Galway Education Department (now The School of Education, University of Galway) and a thin outline of its growth over more than eighty years. Further study be needed to consider the contribution of the Lecturers and Centre/Course Directors who were responsible for so much development and innovation within the Department.

In particular, any note on the beginnings of the Department must refer to Professor Patrick Larkin, second holder of the Chair (1925-67) and College Bursar (1946-65). Much more research will be needed in order to do justice to his very considerable and lengthy contribution to the development of the Department.

His appointment as Professor was particularly welcomed by the students. The U.C.G. Annual of1925/6, a publication of the Literary and Debating Society, wrote of him in its chronicle (p 11): 'Remembering the active part which, as a student, he took in College affairs, we cordially congratulate him, and wish him every success in his new sphere of activity'.

Alone in what was even then a complex Department, he built well on the foundation laid by Ó Ceallaigh. His contribution was essential in the success of the new Degree courses for National Teachers in the late twenties, and he presided over the appointment, in 1931, of the first Lecturer in Education through Irish. Former students of Professor Larkin remember his gentle but skilful professional training of secondary teachers, and his practical emphasis on the value of audio-visual aids to teaching. He was a pioneer in what came to be called the 'technology of education'. Later, when UCG bought the Grammar School on College Road, a room there became his Department's workshop, where students learned even the basic skills of using a fretsaw to create maps from plywood. Old style magic lantern slides and l6mm sound films have survived as a record of this pioneering stage of educational technology.

^ Hide answer

Note: The following article was written, shortly before his death in 2001, by an tAthair Eustás Ó Héideáin O.P., Professor of Education at NUI, Galway from 1968 - 1988

Note: The following article was written, shortly before his death in 2001, by an tAthair Eustás Ó Héideáin O.P., Professor of Education at NUI, Galway from 1968 - 1988

Almost seventy years ago the University College Galway Act 1929 noted that the College 'has lately made provision by statute for securing that certain of the professors and lecturers of the said College shall deliver their lectures in the Irish language and proposes to take such further steps as circumstances may permit to secure that an increasing proportion of the academic and administrative functions of the said College shall be performed through the medium of the Irish language'.

Almost seventy years ago the University College Galway Act 1929 noted that the College 'has lately made provision by statute for securing that certain of the professors and lecturers of the said College shall deliver their lectures in the Irish language and proposes to take such further steps as circumstances may permit to secure that an increasing proportion of the academic and administrative functions of the said College shall be performed through the medium of the Irish language'.